What Do the New Health Advisories for PFAS Mean for Water Utilities?

By Jack Ding

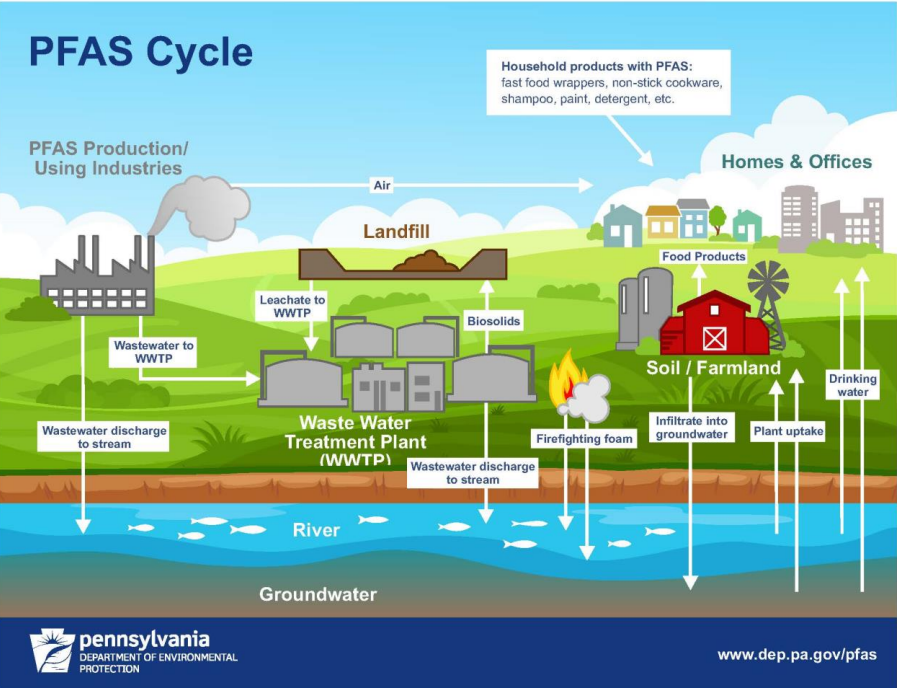

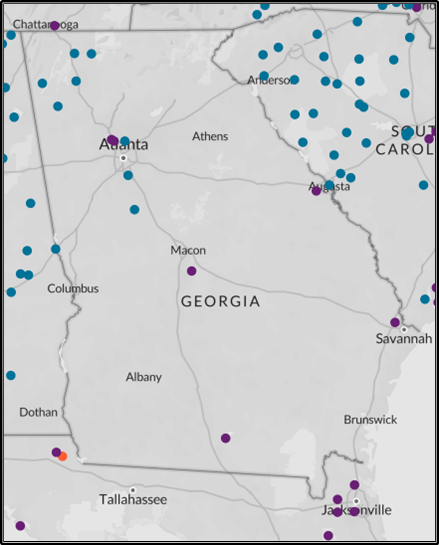

Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS) are a group of “forever” chemicals widely used in manufacturing processes such as textile, fabric, carpet manufacturing, and water and heat-resistant coating. PFAS are carcinogenic, and due to them containing a strong chemical bond, PFAS compounds are very difficult to break down or degrade once released into the environment. PFAS contamination is prevalent across the country. Environmental Working Group, a non-profit organization, estimated that there are over 2,800 contaminated sites in 50 states and two territories in the U.S., and 13 of those sites are in the state of Georgia [See map below]. Thus, regulating PFAS has been a priority for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). However, the most recent health advisories (HAs) for certain PFAS chemicals have stimulated much discussion among water utilities, lawyers, scientists, activist groups, and the public in general. In this blog post, we will interpret and clarify the new HAs, and discuss how the stricter HAs could potentially impact the operational cost for utilities, ultimately affecting the water bill for customers.

On June 15th, EPA released the interim updated Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) HAs and final HAs for two other chemicals, Perfluorobutane Sulfonic Acid (PFBS) and GenX (Hexafluoropropylene Oxide (HFPO) Dimer Acid and its Ammonium Salt) chemicals. It was an important step along the PFAS Strategic Roadmap: “EPA’s Commitments to Action 2021-2024” issued by the EPA to protect people’s health from existing or new PFAS contamination in drinking water. Water utility professionals are concerned about two implications of the new health advisory levels for PFOA and PFOS (two specific compounds in the PFAS family):

The proposed level of 0.004 parts per trillion (ppt) for PFOA and 0.02 ppt for PFOS are too low to be detected even by the laboratories that met the fifth Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR 5) [2]. The UCMR minimum reporting level is four ppt for both PFOA and PFOS.

The cost of sampling, monitoring, and treating drinking water to reach the new health advisory level of PFOA and PFOS is too high for drinking water systems across the country.

Figure 2. Estimated PFAS Contamination Sites in the state of Georgia [1]

First, it is worth noting that the HAs currently issued by EPA are non-enforceable and non-regulatory. This means that there is no immediate action required by the EPA. However, the EPA is expected to announce the proposed national drinking water regulation for PFOA and PFOS by the end of 2022, and the finalized rules and regulations are expected by the end of 2023 [4]. From now until the EPA finalizes rules, no action is required but utilities should make sure they are well-informed and continuously tracking this issue.

One major takeaway of the new HAs is that the proposed levels are significantly lower than existing HAs for PFAS. It indicates that EPA is taking strong actions to address the contamination issues of PFAS and taking responsibility to protect people’s health and wellbeing as they understand more about the negative health effects. However, there are challenges related to enforcement of this new level. EPA stated that they are working on new sampling and monitoring methods for the laboratories to detect lower levels of PFOA and PFOS in drinking water. However, using the example of PFOA, going from 4 ppt of the current minimum reporting level to 0.004 ppt means that the new method needs to be 1,000 times more sensitive to detect the presence of PFOA.

The development of such a method to detect PFOA at this low level raises several challenges

performing such tests could be expensive and the method must be affordable to be feasible for water utilities nationwide, and

the margin of error needs to be relatively small in order to prevent false positives or negatives.

For example, the result could be 0.003 ± 0.04 ppt. And in that case, it will be hard to determine whether it’s a violation or not because the margin of error is ten times larger than the threshold. Previously, if a violation occurred, primacy agencies would require more follow-up tests until the system went back into compliance. A test for typical contaminants other than PFAS is around $20 to $150 per test [4]. Tests for PFAS could be much higher due to the ultra-low maximum contaminant level.

Water utilities have been concerned about these new HAs because of the ultra-low threshold and the additional cost to sample, monitor, and enforce the HAs for PFAS. The updated 2022 HAs lowered the minimum contaminant levels of PFOA and PFOS from both 70 ppt in 2016 to 0.004 ppt and 0.02 ppt, respectively. It is important to note that this action was advised by new scientific findings that the PFOA and PFOS have negative health impacts at levels much lower than 70 ppt [3]. PFOA and PFOS have been associated with effects on the immune and cardiovascular system, fetal development (e.g., lower birth weight), and cancer. While it is crucial to treat water to a safe level of PFOA and PFOS, especially to protect the most vulnerable groups such as immune-compromised patients and pregnant women, the cost to upgrade infrastructure to achieve such a level may be unaffordable for utilities. It requires granulated activated carbon or reverse osmosis to remove PFAS from the drinking water, and currently, most drinking water systems do not use such technology. Reverse Osmosis is commonly used in water-scarce regions to convert seawater into potable water. Activated carbon is commonly used in households at their home water filtering system (e.g., Brita water filter), but it needs to be replaced frequently and can be of additional financial burden.

Financing for PFAS

The federal government is providing financial assistance under President Biden's Bipartisan Infrastructure Law specifically addressing PFAS and other emerging contaminants in small and disadvantaged communities. A total of $5 billion has been allocated through state revolving fund (SRF) programs to assist these communities in reducing exposure to these chemicals through their drinking water.

In Georgia, $17.8 million will be available for emerging contaminants in 2022, specifically. However, more general pots of funds can also be used to address PFAS. For example, the traditional or “base” State Revolving Fund (SRF) dollars is also eligible for PFAS remediation. Utilities can find more ways to tackle the financial implications of new rules from this earlier post “What Might New Water Quality Regulations Mean for Utility Finance?” Utilities should also stay closely tuned for announcements from the state with details on finance opportunities.

This is part of a blog post series funded by the Georgia Environmental Finance Authority (GEFA).

Disclaimer: The opinions of the writers should not be considered legal advice or endorsement by GEFA.

[1] Environmental Working Group. (2022 June 8). PFAS Contamination in the U.S. https://www.ewg.org/interactive-maps/pfas_contamination/.

[2] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022 December 14). Questions and Answers: Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA, PFOS, GenX Chemicals and PFBS. https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/questions-and-answers-drinking-water-health-advisories-pfoa-pfos-genx-chemicals-and-pfbs#q12.

[3] U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2022 June). Webinar on Drinking Water Health Advisories for Four PFAS (GenX, PFBS, PFOA, PFOS) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Announcement. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-07/PFAS%20HAs%20for%20Water%20Utility%20Briefing%20-%20June%2022Final.pdf.

[4] Santanachote, Perry (2019 September 26). How to Test Your Tap Water. Consumer Reports. https://www.consumerreports.org/water-quality/how-to-test-your-tap-water-a1537953804/.

Subscribe Here

Sign up with your email address to receive notices of new blog updates. We post about once per month.